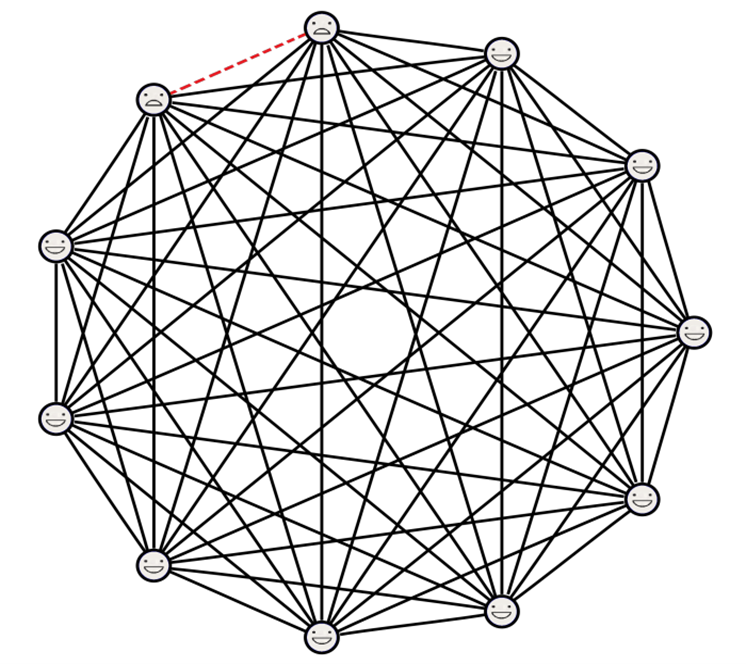

August 2023, first semester of university. My friends and I are cooking for a group of twenty five first year Bachelor students. We think we’re cooking just enough. A few laughs and giggles later, we gaze at the leftover food; did we eat anything at all? There’s enough left for at least another thirty people!

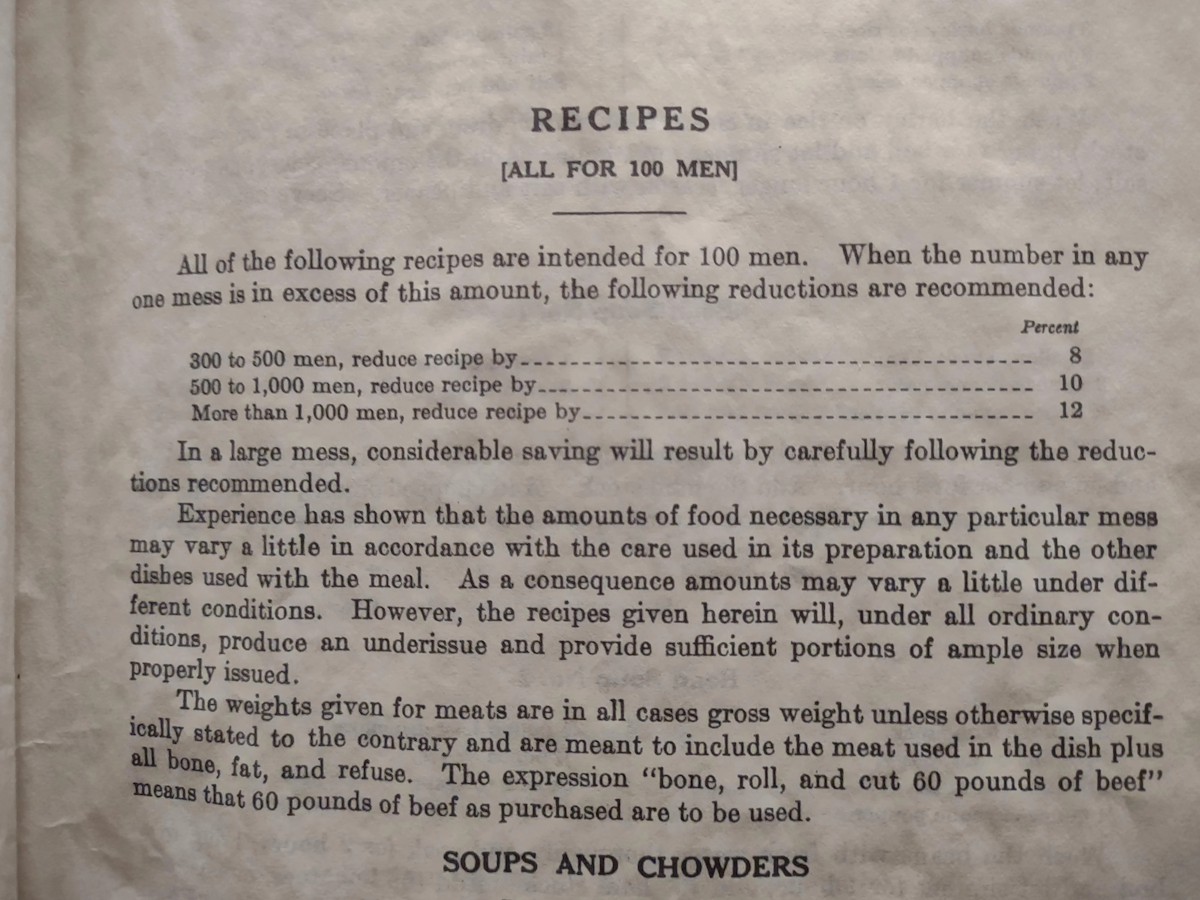

Shortly after this epic failure, I was browsing Reddit when I stumbled upon an ancient relic: a 1940 U.S. Navy cookbook with recipes for 100 people each (see the pictures below). Could this book teach me how to prevent another such catastrophe?

What caught my eye was a page about reductions. It says that if the group is large enough, you can reduce the recipe’s amounts by some percentage. For instance, if you’re cooking for 1000 people, you can reduce the ingredients by 10%. This means the following: you are inclined to multiply the ingredients of a 100-person recipe by 10 to feed  people. The reduction tells us that it suffices to multiply by 9.

people. The reduction tells us that it suffices to multiply by 9.

Pictures posted on Reddit by u/AngryHorizon under the title “My Grandpa’s US Navy Cookbook from 1940 during his time as a US Marine.”

Why does this work? User u/Elitejack suggests:  I imagine it's because the small losses as you're cooking are, by proportion, less as you scale up.

I imagine it's because the small losses as you're cooking are, by proportion, less as you scale up. This sounds reasonable, but I doubt it justifies such notable reductions. I have another hypothesis: to be on the safe side, the recipe prescribes too much. As the group size grows, the likelihood of encountering many people with a large appetite drops. Hence the recipe can be reduced. This intuition is supported by a famous mathematical result: the Central Limit Theorem. Can this explain the recommended reductions? If you join me as a chef on the submarine U.S.S. Alexandria, perhaps we can figure it out together?

This sounds reasonable, but I doubt it justifies such notable reductions. I have another hypothesis: to be on the safe side, the recipe prescribes too much. As the group size grows, the likelihood of encountering many people with a large appetite drops. Hence the recipe can be reduced. This intuition is supported by a famous mathematical result: the Central Limit Theorem. Can this explain the recommended reductions? If you join me as a chef on the submarine U.S.S. Alexandria, perhaps we can figure it out together?

Welcome aboard the U.S.S. Alexandria

It's our first day as chefs on the U.S.S. Alexandria, a U.S. Navy submarine with a crew of about 100! Are you excited? How much should we cook?

We will only know after we served the first meal how big the appetite of this crew is today. Luckily, the Navy knows how much food an average crew desires. Let's denote by  the average appetite given by the Navy, in pounds.

the average appetite given by the Navy, in pounds.

So should we simply cook  pounds? That scares me! What if the crew happens to be extra hungry today? Before we know it, an angry crew of big marines will be banging their cutlery on the table shouting

pounds? That scares me! What if the crew happens to be extra hungry today? Before we know it, an angry crew of big marines will be banging their cutlery on the table shouting  Hungry!

Hungry! . On the contrary, if the crew is less hungry than usual, we'll have many leftovers that end up being thrown out. I think we should take into account how much the crew's appetite tends to deviate from

. On the contrary, if the crew is less hungry than usual, we'll have many leftovers that end up being thrown out. I think we should take into account how much the crew's appetite tends to deviate from  .

.

There are many ways to measure deviation. A common way of measuring it is using the standard deviation. Essentially, we ask ourselves  How much, on average, does the appetite on some day differ from

How much, on average, does the appetite on some day differ from  ?

? We don't care whether the appetite is above or below average; a difference is always positive. However, there's a catch: large differences weigh more heavily in this average and small differences weigh less. Still, the standard deviation gives us an idea of how large the difference tends to be. We denote the standard deviation by

We don't care whether the appetite is above or below average; a difference is always positive. However, there's a catch: large differences weigh more heavily in this average and small differences weigh less. Still, the standard deviation gives us an idea of how large the difference tends to be. We denote the standard deviation by  . Question to you: how much should we cook?

. Question to you: how much should we cook?

Maybe you thought  pounds. That sounds alright, but I’m not convinced. Some days they might want

pounds. That sounds alright, but I’m not convinced. Some days they might want  pounds, or even

pounds, or even  pounds. Intuitively, if we cook more, we are less likely to run short. So somewhere we should draw the line. Where?

pounds. Intuitively, if we cook more, we are less likely to run short. So somewhere we should draw the line. Where?

Let's make an assumption: that one's hunger is independent of another's hunger. Why this is important is outside of the scope of this article, but would become clear in a course on probability theory. When we do, the so-called Central Limit Theorem applies. It tells us that the crew's appetite on a given day is (approximately) a normal variable. Equivalently, we say it follows a normal distribution. Essentially, the behavior of the crew's appetite is completely characterized by  and

and  ; if you know these values, you can compute all kinds of probabilities.

; if you know these values, you can compute all kinds of probabilities.

It is at this point that the Commander knocks on our kitchen door to hand us the cookbook.

The cookbook works well

The clock is ticking. We pick a recipe and get cooking. Soon, the crew is gobbling up our fresh butter chicken and the lovely, warm smell lingers in the hallway all week. It's a success! We do this every day for the next month and all is well. Only once in these thirty days we cooked too little; the crew was not happy, but the Commander assured us that this may happen from time to time, just not more than once a month. Most of the time we had a lot of leftovers. Sadly, the fridge barely fits a chicken, so most leftovers were thrown out!

Three months in, the Commander asks us to cook for the U.S.S. Anchorage, with a crew of about 400. We pick our favorite recipe, a creamy, spicy chili with rice, and are inclined to cook 4 times the ingredients. But we don't want four times as many leftovers as we typically have.

Can we prevent this? Most of the time, the recipe for 100 provides plenty. Perhaps we dare say that 19 out of 20 times it is enough. Let's denote by  the appetite of the U.S.S. Anchorage crew on some day. Suppose the recipe prescribes

the appetite of the U.S.S. Anchorage crew on some day. Suppose the recipe prescribes  pounds of food. Then we could assume that the probability that

pounds of food. Then we could assume that the probability that  is at most

is at most  , is

, is  . Equivalently, the probability that

. Equivalently, the probability that  exceeds

exceeds  , is

, is  .

.

We saw that  is normally distributed. The normal distribution tells us that the recipe should prescribe (at least)

is normally distributed. The normal distribution tells us that the recipe should prescribe (at least)  pounds to get this

pounds to get this  certainty. The number

certainty. The number  seems to come out of thin air, but it's actually a property of the normal distribution;

seems to come out of thin air, but it's actually a property of the normal distribution;  of the time, a normal variable will be at most

of the time, a normal variable will be at most  , no matter the value of

, no matter the value of  and

and  . We therefore assume that \begin{equation} r = \mu + 1.65\sigma, \end{equation} meaning we assume the recipe book authors were clever and that they made sure the recipe provides enough the majority of the time.

. We therefore assume that \begin{equation} r = \mu + 1.65\sigma, \end{equation} meaning we assume the recipe book authors were clever and that they made sure the recipe provides enough the majority of the time.

Scaling up!

Recall  is the appetite of the U.S.S. Anchorage crew, consisting of 400 people. Again we want

is the appetite of the U.S.S. Anchorage crew, consisting of 400 people. Again we want  certainty that we cook enough. Now

certainty that we cook enough. Now  is essentially the appetite of four groups of 100 people added together. A fascinating property of the normal distribution is that the sum of (independent) normal variables is again a normal variable. So

is essentially the appetite of four groups of 100 people added together. A fascinating property of the normal distribution is that the sum of (independent) normal variables is again a normal variable. So  is also normally distributed!

is also normally distributed!

It is also known that this sum  has average

has average  and standard deviation

and standard deviation  . Using the same reasoning as before, we find that the recipe for 400 people should prescribe \begin{equation} 4\mu + 1.65\sigma\sqrt{4} \end{equation}

. Using the same reasoning as before, we find that the recipe for 400 people should prescribe \begin{equation} 4\mu + 1.65\sigma\sqrt{4} \end{equation}

pounds. This is equivalent to saying the recipe should prescribe 4 times a reduced recipe! To see this, we need to do a bit of mathematical work.

The cookbook knows all

The result we found above holds no matter the values of  and

and  , given that the assumptions are true. But it is clearly in a different form than in the book.

, given that the assumptions are true. But it is clearly in a different form than in the book.

To translate our result into one like the book, we need to know the ratio between  and

and  . Sadly, I don't remember the values of

. Sadly, I don't remember the values of  and

and  that I was told on our first day; we've been using the cookbook ever since. I can, however, deduce this ratio by combining our result and the numbers given in the book. Let me do that! I will deduce it based on the reduction for 300 people. Does our result align with the given 500-person and 1000-person reductions? Judge for yourself!

that I was told on our first day; we've been using the cookbook ever since. I can, however, deduce this ratio by combining our result and the numbers given in the book. Let me do that! I will deduce it based on the reduction for 300 people. Does our result align with the given 500-person and 1000-person reductions? Judge for yourself!

| Group size | Reduction in the book (percent) | Our reduction (percent) |

| 300 | 8 | 8.0 (by construction) |

| 500 | 10 | 10.5 |

| 1000 | 12 | 12.9 |

Seeing the enormous amount of leftovers I had back in August 2023 at the start of the semester, I don't think these results would have saved me. Nevertheless, if I am ever cooking for a huge group, I'll use a proper cookbook and apply these reductions!

Thumbnail by August de Richelieu.