Rafael Prieto-Curiel is a mathematician and a faculty member at the Complexity Science Hub in Vienna, Austria. His research focuses on crime, mobility, migration and urban dynamics. He also consults the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and the World Bank, where he does a spatial and demographic analysis of cities.

Rafael studied mathematics in Mexico City. After his studies, and a very short career in finance which he didn't find very appealing, he started working in the police department of Mexico City. In 2013 he started a master’s degree at the University College London followed by a doctorate degree focusing on Mathematical models of crime, fear, migration and road accidents. Besides his research, Rafael has been very keen on science communication. Among others, he has been one of the founders and editorial director of magazines Chalkdust and Punto Decimal Mx, and the editorial director of Laberintos & Infinitos. His broad interests and achievements sparked our interest to meet him and chat about his mathematical endeavors.

It's a great pleasure to meet you Rafael and have this chat with you. To start, could you tell us some things about you and the steps that have led you to the current position you have?

It is also a great pleasure to meet the people behind the Network Pages! My name is Rafael Prieto-Curiel and I am from Mexico. In Mexico it is typical that we have two surnames, Prieto from my father and Curiel from my mother. I'm a mathematician by training from Mexico City, where I was born and I grew up. After my bachelor's, I started working in finance. It turned out not to be a fit for me. So I applied at the Mexico City Police and got a job with a lower salary and longer hours, but knowing that I will be working for my city, my friends and family. To be honest, my mother was not so happy at all in the beginning with this decision!

I started working for the Mexico City Police not as an officer, but as a mathematician. When I introduced myself to the people in the police, they would respond with "What are you doing here?", "What?" or "How can we use mathematics here?" They were all challenging me. I needed to convince them that mathematics is a useful tool for the police.

In the beginning, I had to make reports for the mayor presenting data about crime. There was not even statistics involved, it was simply reporting numbers. We mathematicians are quite lazy and obsessed with efficiency, so I automated the whole process. When my boss saw that it took only 20 minutes for a report rather than 12 hours, he told me: "No, no, what else are we going to do? You cannot finish your report at 9:00 AM and then do nothing the rest of the day." That's when I started doing crime analysis by myself.

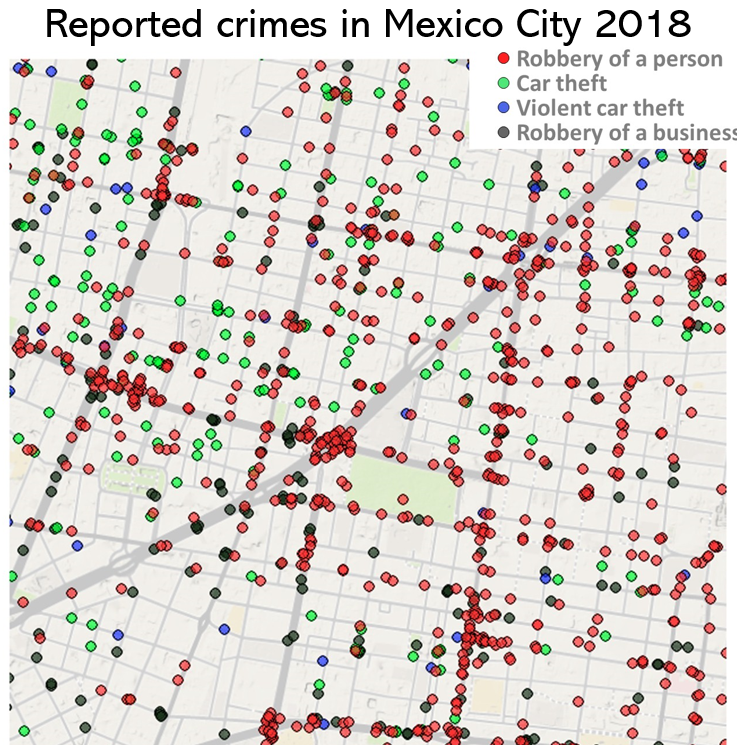

I started as follows. Imagine a map of the city, say Mexico City, and you put a pin every time a crime gets reported. You will see there are places with a lot of crime, places with little crime. There are 'hot' moments with more crime and 'cold' moments with fewer crime. And not the whole city gets hot and cold at the same time. I made a system that does this automatically and allows you to monitor crime in real time. Working on this, I got promoted. I was assigned a team of mathematicians, economists, engineers, and more. We also had forensic experts and a person from the army in our team. Our goal was to instruct police officers strategically to reduce response time, the time for officers to get to a crime.

A map showing where crimes occured in Mexico City in 2018. A circle (pin) corresponds to one crime.

We wanted to automate this, too. That is a lot harder than automatically creating a report with numbers and graphs, because you need to process a lot of data and find an optimal strategy for where to place officers. But our work was successful. Before, the response time was around 17 to 20 minutes. With mathematics, we reduced it 4 minutes!

I can imagine the police, the policymakers, the mayors are perhaps skeptical about a more mathematical approach to fighting crime. How did you experience this?

I learned two important lessons. First, you cannot, as a mathematician, have an ego. We mathematicians usually have an ego, right? We may think: "I'm going to save the world with this equation." Well, not exactly. Let's talk to an expert first. Listen to what they have to say. If you want to help with mathematics you need the opinion of the crime scientists and the police officers. "Why did a crime happen there?" and "why not there?". Put differently, working interdisciplinary is very important. On the other hand, theories that arise from experience may not be true. A police officer may say: "A crime happened here because there is a bank nearby." With data and mathematics you can determine whether this theory is true. Perhaps it is other factors driving this crime.

The second lesson is that communication is very important. Often, mathematics is perceived as tricky and complicated. Even worse, it can be perceived as being not useful to society. But this is not true! The challenge is to explain the power of mathematics as a tool. Because in the end, I see mathematics as a tool. I was lucky to get in touch with mathematics communication early on.

During my bachelor's in Mexico City, I noticed some printed editions of a mathematics magazine called Laberintos & Infinitos. But the magazine was dead. They hadn't published for several years. So I decided to revive it! And throughout managing it I learned to communicate mathematics.

The logo of Laberintos & Infinitos.

Why did you decide to leave the police?

I worked for the police for five years and I still consider it the job of my life. However, the biggest question I had when working for the police was: "Why can't we convince people that the city is safer?" I always assumed that, if there is less crime, people will feel safer. This was my perception. But it is false. Mathematics helps you position your resources strategically. By reducing response times and optimally allocating police officers in the city, we got the police closer to the crimes. But more arrests doesn't necessarily make people feel the city is safer! How people feel about crime is a more complex phenomenon which I wanted to understand better. That's when I chose to start a PhD in applied mathematics and opinion dynamics at University College London.

My topic was precisely trying to model fear of crime as a process of opinion dynamics in a network. Essentially, I simulated a population in which some people suffer from crime, others don't, and included fear of crime and the ability of people to influence each other. After having worked on this simulation carefully, I tried something. I doubled the amount of crime in my simulation and I observed that the fear of crime stayed exactly the same. That is when I knew there was something to be uncovered here and I needed to research further. This result was my Eureka moment and I knew I had a PhD. After my PhD, I did a Postdoc in Oxford, analyzing social dynamics, crime and terrorism in Africa.

In 2024 you were awarded the Science Breakthrough of the Year award in the Social Sciences & Humanities category for your research on on drug cartel dynamics in Latin America. Could you tell us about this research?

In Mexico we have a big problem with drug cartels. In 2012, when I left Mexico for London it was a time where Mexico City was extremely dangerous. There were many homicides and I still remember the former president, Felipe Calderon, announcing that we shouldn't be concerned. These were just cartel members killing each other and that eventually cartels should reduce and disappear because they will just eliminate each other. In 2015 the president said the same thing, and in 2020 as well. But the number of homicides by cartel members kept increasing. We were missing something. I started visualizing the data that was available about the five largest cartels in Mexico, mostly data about homicides carried out by their members. I observed there were no signs the cartel sizes were decreasing, so I kept working on it and eventually I made a mathematical model consisting of 150 coupled differential equations modelling the sizes of the 150 cartels in Mexico. In this model members join a cartel due to recruitment, and they leave a cartel because they are arrested, killed, or just retire.

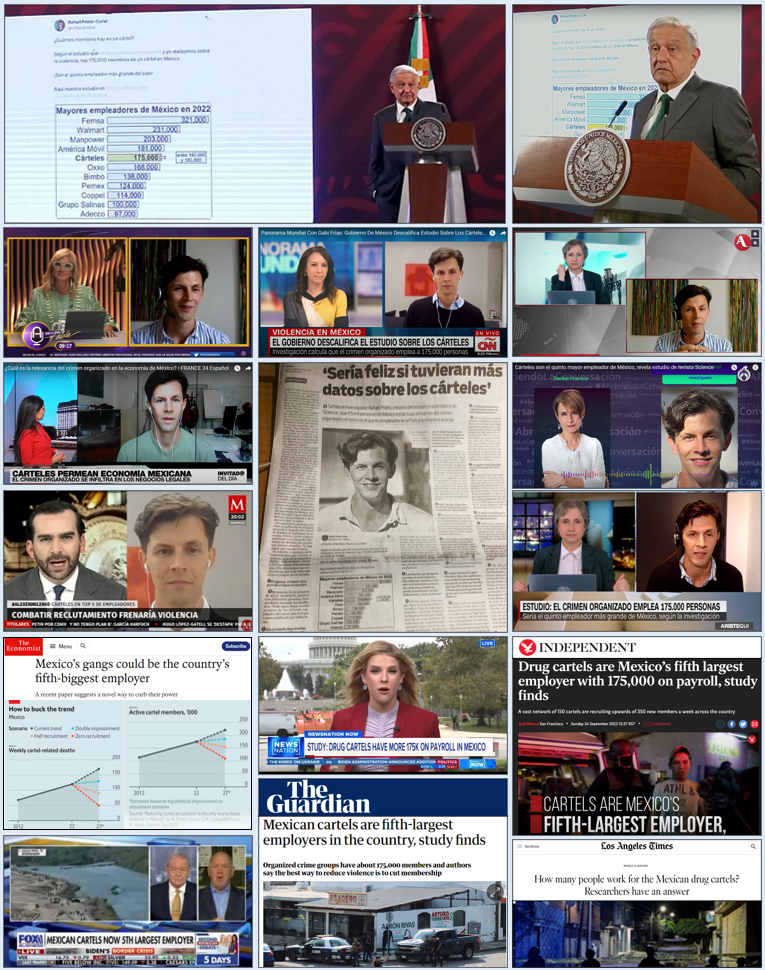

Using this mathematical model and the data that was available, we showed that only arresting more cartel members will not shrink the cartel. Even if you arrest twice the number of criminals, in five years Mexico will still be more violent than today. Why? We estimated based on our model that cartels in Mexico employ almost 175.000 people, and recruit 250 people per week, making them Mexico's fifth largest employer! This research was published in Science in 2023, and it sparked a broad discussion. This was one of the trickiest results in my career. I presented our results to experts and I was invited on national media to discuss our findings. That was a very intense period because as a mathematician I was never trained to speak on national television. But it was important to do it.

Various media coverage of Rafael's research.

To stop the growth of the cartel, we need to reduce their recruitment capability. The discussion that arises is how to do this. We are used to arresting cartel members, but it is not entirely clear how recruitment can be halted. What we do know is that many people choose becoming a cartel member despite the great risks. We are trying to understand, also quantitively, why that is. Decreasing cartel recruitment is a very complex societal endeavor. I think it is important to invest more in social programs so that people feel they have an alternative.

During your career it has been very important to discuss with people with different backgrounds, from police officers to politicians and journalists. You also said that as a mathematician you didn't always feel prepared to talk to the media. At the same time you were involved with various science communication initiatives. What can you do as a mathematician?

I really love talking about mathematics and my research. And it is important that we make mathematics more accessible, because it is a very strong tool. I want to share a story from my PhD. The first months of my PhD were very challenging. I was going to seminars and conferences and barely understood the titles of the talks. I felt lost and that I was not in the right place. I submitted a paper that was rejected, which had an impact on my motivation. Now I am less affected by it, but in my first steps it was demotivating. And we tend to not talk about these things.

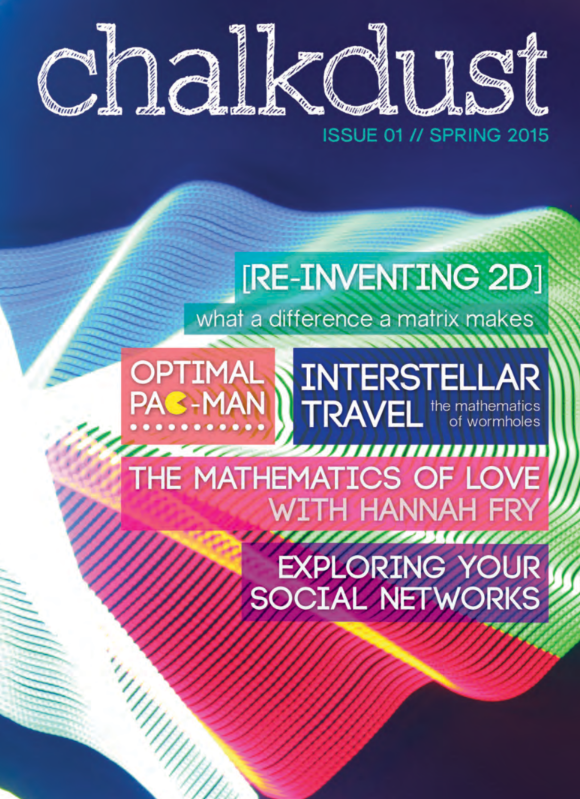

After some months I went back to Mexico and I was thinking about quitting, maybe I would start working at the police department again. When I went back to London I took some issues of Laberintos & Infinitos with me. I decided to give one more chance to my PhD, three more months and then I would quit if it didn't work out. I proposed to some colleagues in London to start a magazine about mathematics in English, like Laberintos. And this is how Chalkdust was born! For the first issue we interviewed Hannah Fry, which was amazing! We had also received 500 pounds to print some copies and distribute them in the various mathematics departments.

The cover of the first issue of Chalkdust published in March 2015.

The cover of the latest issue published in March 2025.

The most important question was: "Who is the audience?". For Chalkdust our audience were the authors themselves. We have published articles by more than 400 authors, and most of them published for the first time a article for a broader audience. We stimulated young mathematicians to write, because we believed the training process with an editor is very valuable. And they would have a publication which would enrich their portfolio.

Working on Chalkdust was amazing, I was the main editor for three years. From the first moment I wanted to establish the idea that we would not do this forever. We should pass it on to new editors after some time. I thought this was the problem with Laberintos, it depended too much on one person. It is important to create institutions which don't depend on specific people. And I think we achieved this with Chalkdust!

Sometimes an interview consists of many questions. Sometimes, you simply get to listen. Rafael is an excellent storyteller and he had us hooked from the first minute all the way to the end. To this day, Rafael continues to tackle complex societal issues with mathematics. At the same time, both Larerintos & Infinitos and Chalkdust are alive and well, inspiring people from across the globe every day with storytelling. While Rafael insists on creating institutions rather than celebrities, we think his work and words deserve fame.