This is the first article in a series. Last year, Anne-Fleur Dijkhorst won the 2024 CWI Best Thesis in Applied Math Award. In the next article, a contestant of the 2025 CWI Best Thesis award will write about their research.

"Pollution from plastic waste is a major problem that is increasingly gaining attention. As soon as plastic waste ends up in water, it becomes increasingly difficult to clean up. It harms surrounding ecosystems, breaks down into microplastics, and often enters our bodies through drinking water and food. Research has shown that a significant portion of plastic reaches the ocean via canals and rivers1. That’s why it’s important to capture the waste closer to its source, in these canals and rivers," Anne-Fleur Dijkhorst writes in Dutch magazine STAtOR. Anne-Fleur studied Applied Mathematics and Applied Physics at Delft University of Technology. Her thesis revolved around using a mathematical model to help clean plastic waste from canals and rivers. What did her research entail?

In the original Dutch article, Anne-Fleur writes about doing her thesis in collaboration with Noria, a tech scale-up from Delft that tackles 'urban plastic soup'. "At Noria, they cherish the beauty of nature in general and of water in particular. They want to preserve that beauty for future generations, using their passion for developing sustainable solutions. They don’t just tackle plastic consumption; they focus on litter. They do this by researching the location and flow of plastic waste in local waterways and by removing the waste with the help of two different types of capture systems that they have developed themselves," Anne-Fleur explains.

On the left is the 'CirCleaner', a "cleverly designed system suitable for removing plastics from the water at pumping stations, canals, and rivers in a sustainable and fish-friendly manner," according to Noria's website. A video of the machine in action can be found here. Anne-Fleur writes that it is a moving, solar-powered wheel that scoops waste out of the water and into a container. The 'CanalCleaner', on the right, is a passive device that catches the plastic and prevents it from escaping back into the water.

To catch the most waste, it is important to place these devices in strategic locations. This is what Anne-Fleur investigated: how can these two devices be placed such that the amount of waste caught is maximized. Her approach was to build an optimization model that helps decision makers decide where to best place the machine.

How does that work? Noria already had a way of predicting where a lot of plastic would get stuck in the water. "This system used the origin of plastic waste, the wind direction, the geometry of the waterway (for example sharp bends), and vegetation along the shore or in the middle of the water to make its predictions. Sometimes the flow of the water was also considered, for instance if there was a pumping system nearby. But based on tests and conversations with local experts, the movement of plastic waste in canals and waterways seemed to depend mainly on the wind," Anne-Fleur writes.

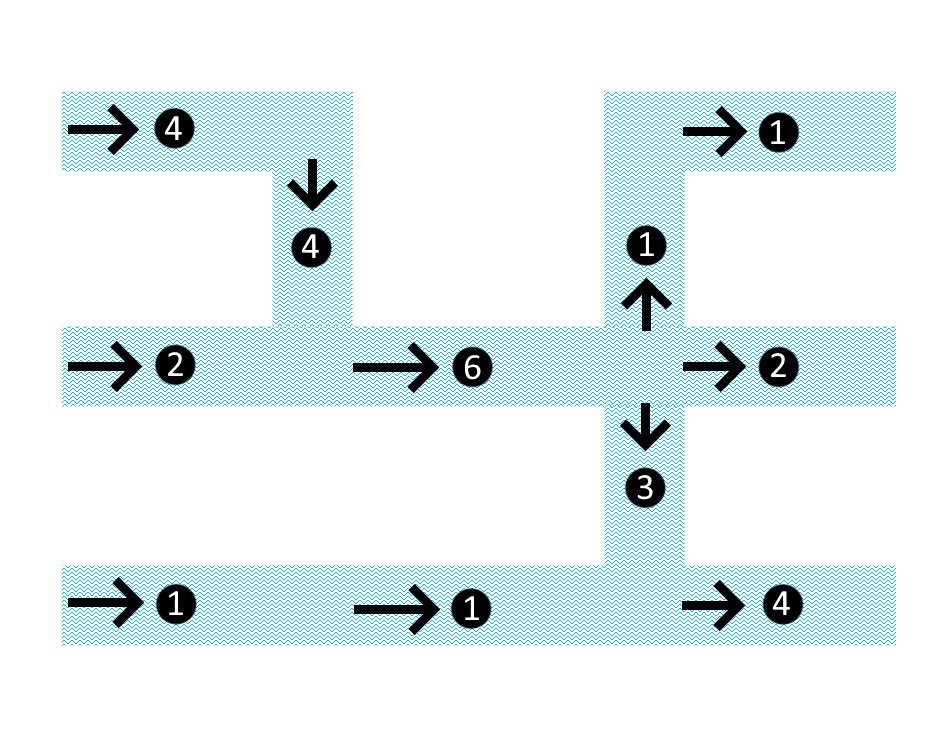

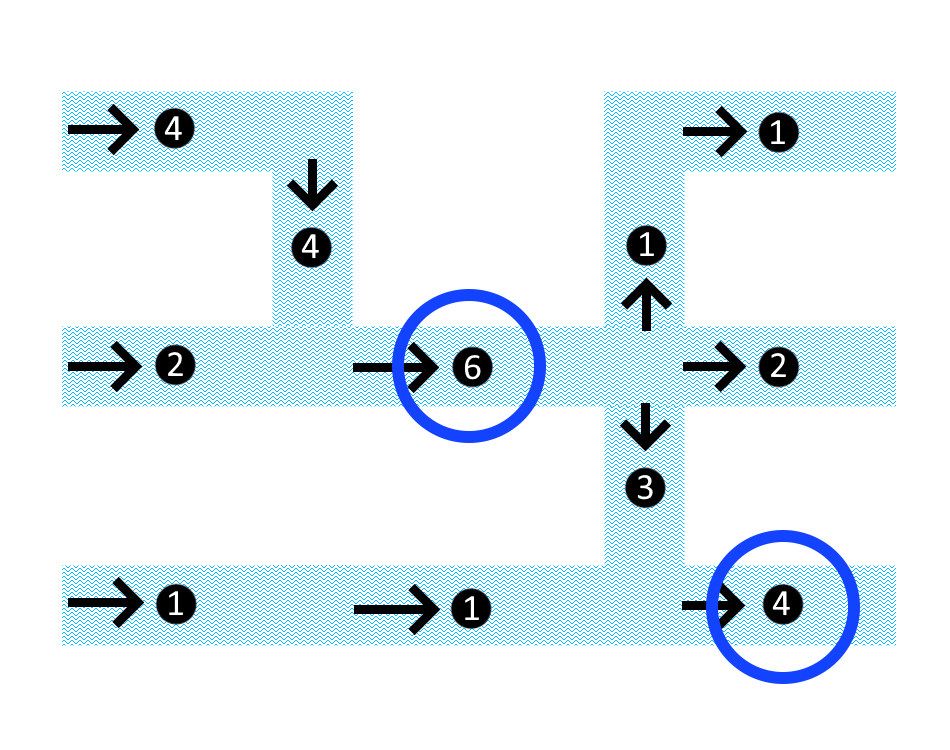

Knowing where plastic soup tends to emerge is not enough to make a good decision. This knowledge needs to be translated into a strategic placement. Here, performing calculations on a mathematical model can help. Let's have a look at what such a mathematical model for this problem could look like. Below is a fictional canal network. Waste comes in from the left, and leaves on the right.

An example of a flow network. The canals are marked blue, possible locations for cleaning machines are marked with black dots. The arrows indicate the direction in which water flows.

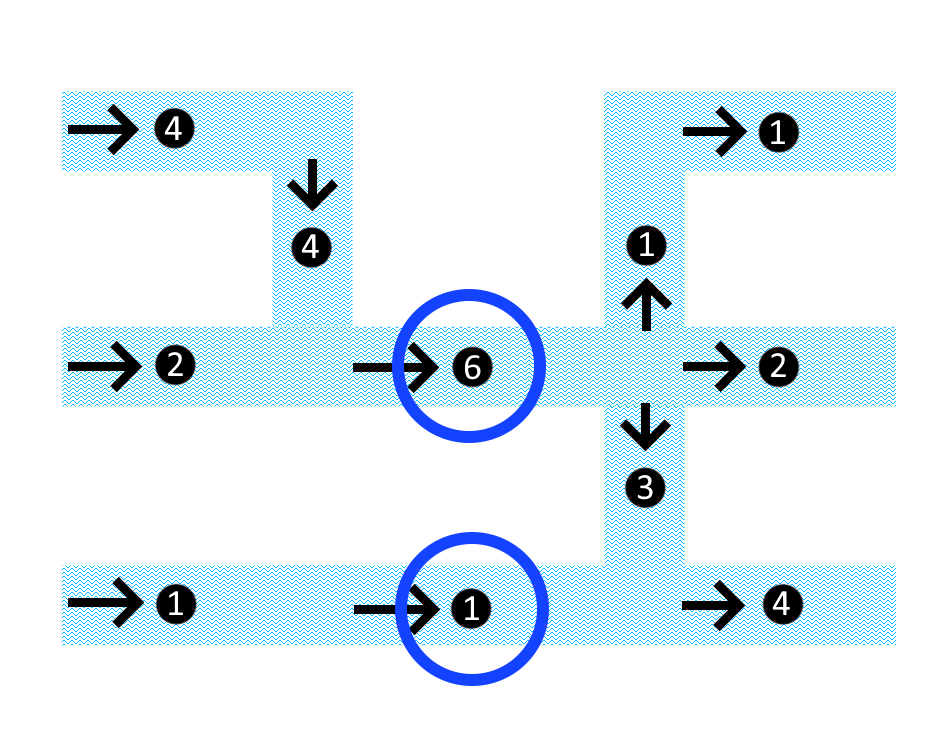

Let us assume in this fictional example that a machine catches all the waste that passes by. If you wanted to place as few machines as possible to catch all of the waste, then there are two options for the placement of machines. Both options are depicted below, on the left and on the right respectively.

In both scenarios, all waste is caught using two machines. In reality, the machine may not able to catch everything; some of the waste passes by! With this in mind, the option on the right is favorable.

This problem, that of finding the least number of locations (and which locations exactly!), is known as the "minimum vertex cut" problem, or the "minimum vertex separator" problem. It is closely related to the "minimum cut" problem. In the minimum cut problem, we don't try to catch waste at the nodes (the dots), but at the edges (the connections between locations & intersections. Not all edges are drawn in this network!). In fact, if you can solve the latter problem, you can solve the former! It turns out that we can solve both problems efficiently, even for large networks.

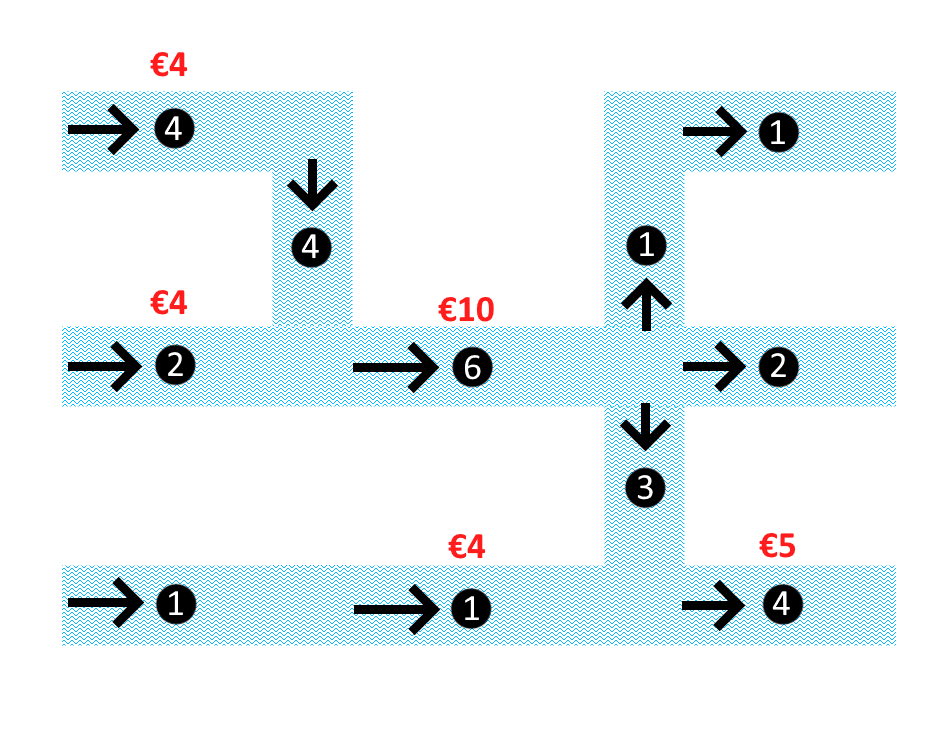

It could be, however, that different placements have different costs. What happens if every location has its own cost? Suppose that some of the locations have been disregarded for practical reasons, and the costs for the others are written in red below:

Neither of the two options from before is the cheapest. The cheapest way to catch all waste is as follows:

Finding a solution with minimum cost can become very difficult, especially if the network is large.

Moreover, this model is not realistic! For example, plastic waste may be deposited into the canals along the way, or plastic waste may be cleaned up by other agents. It is also difficult to determine exactly how much plastic will flow along a possible machine site. As Anne-Fleur writes: "We don’t have data on the exact paths of plastic waste from beginning to end. Fortunately, we can estimate the likelihood of plastic entering the water at a given location, and where plastic from a certain spot will drift to. We do this based on environmental factors such as places where many people spend time along the water (on benches and in parks), and on the basis of wind direction."

The model that she used instead is called the "Flow Capturing Location Problem” (FCLP)". It was studied in 1995 to find optimal placements of gas stations along roads.2 3 This is a similar, but different problem: "One major difference with that setting is that vehicles often make small deviations from their route because they want to refuel. Plastic waste, unfortunately, will not deviate from its path to be collected and must flow exactly past the chosen location. Our problem is more comparable to a situation such as finding the optimal locations for monitoring vehicles (speed checks or weight inspections of trucks)."

Luckily, Anne-Fleur was able to overcome this difference. She also incorporated more aspects than just economic ones: "We adapted the existing model from the literature by adding two aspects: the ability to designate a ‘sensitive area,’ and the ability to use multiple types of collection locations (capture systems). In this context, a sensitive area means that it is particularly important to remove plastic waste from the water in that location. Examples include a nature reserve, or an area where the water (and thus the plastic waste) is moving closer to the sea. The model also incorporates the different characteristics of the two types of capture systems, such as purchase costs and possible restrictions on where they can be installed, for instance due to their size or the lack of power supply for the active system."

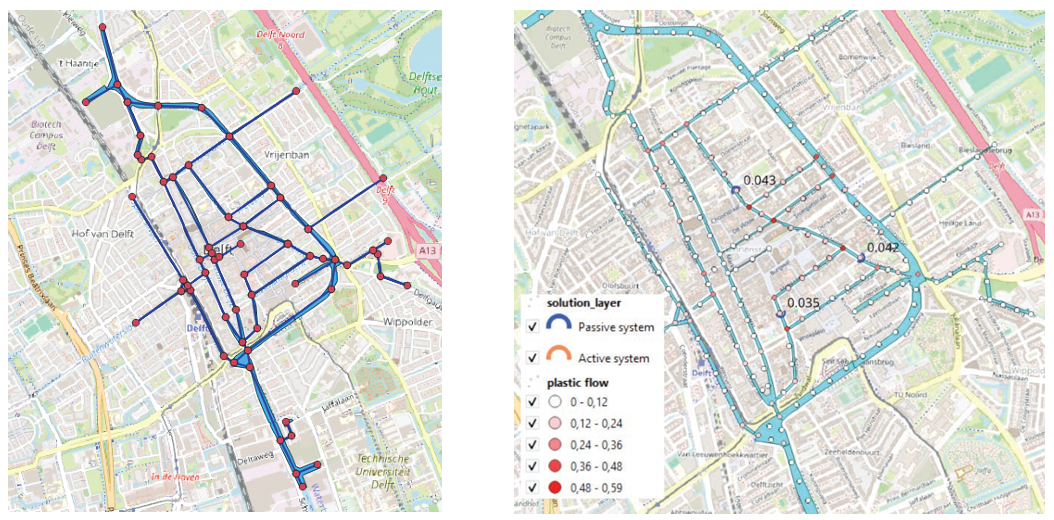

Below are screenshots of the system that she built in QGIS:

Translations in this article were aided by Microsoft Copilot.

References

- L. J. J. Meijer e.a. „More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean”. In: Science Advances 7.18 (2021), eaaz5803. DOI: 10.1126/ sciadv.aaz5803. URL: https://www.science.org/doi/ abs/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5803. ↩︎

- Berman, D. Krass en C. Wei Xu. „Locating Discretionary Service Facilities Based on Probabilistic Customer Flows”. In: Transportation Science 29.3 (1995), p. 276290. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25768694 (bezocht op 13-10-2023). ↩︎

- Berman, D. Krass en C. Wei Xu. „Locating flow-intercepting facilities: New approaches and results”. In: Annals of Operations Research 60 (1995), p. 121143. URL: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/ BF02031943. ↩︎